[Editor’s note: This is an excerpt from TSJ 32.4’s “The Seminar Sessions.” To read the full feature, become a TSJ member today]

Ross Williams and I meet the following morning to outline goals. Over 6-foot and broadly built, the 49-year-old is soft-spoken as we exchange pleasantries. We sit with a pot of coffee, a pitcher of freshly squeezed orange juice, and breakfast buffet items on the table between us.

He’s quick to inform me that we’re missing an important variable for a successful coach-surfer relationship: time. Real results are seen and measured over years, not days. That’ll ultimately dictate our goals. They’ve got to be specific, and they’re on me to set.

“My job is to help you get there,” he says.

I’ve got something, I explain, a deep surfing insecurity: I grew up in a gross Southern California shorebreak—dumpy, short, gutless, windblown. Longer waves, like Sultans, that require linking turns and sections together have always given me fits.

“Do you think that’s really enough?” I ask. I want the full experience.

Williams leans back and chuckles.

“Lots of things will be exposed in between,” he says.

Great, I think.

I then ask him to define his particular approach to coaching, what I should expect from him. “I don’t have a blanket set of rules,” he says. “Everyone’s different. Everyone stands on a surfboard differently. Everyone swings their arms differently. There’s no wrong way to do it. But there’s things in your style and technique that give you strengths and weaknesses. What I try to achieve is identifying weak points and how to improve them.”

His answer hits on the real crux of what we’re doing. It’s not whether coaching works. That’s a resounding yes, evidenced in the use and success of coaching in nearly every activity in which there’s competition or score kept, tennis or golf or baseball—hell, even “business” or “life.” Requirements are a willing student and a coach who knows their stuff. Williams is as fine a coach as any in surfing’s sphere, drawing on decades of knowledge and experience as a touring and free-surfing professional. His track record working with two-time world champ John John Florence and contender Tatiana Weston-Webb, among other elite surfers, speaks for itself.

What I’m after is more philosophical: What benefit does surf coaching offer the average punter?

Surf coaching, in the vein that Williams and many like him practice, is traditionally a service for professionals and the hopefuls. “I work with high-level surfers,” he says, “who are looking for specific info. A lot of it does relate to competing, right? Because that’s when it matters the most: being under pressure and responding how you want to.”

It’s a job inexorably linked to surfing’s professionalization in the 1970s. With surfing a highly lucrative career path, it’s only natural that those on that path would look for any and every edge. Riding waves for a living is an enviable and thus competitive field, after all. Surf coaches—typically former pros themselves who know every inch of the game and with whom a surfer can work over a long period of time in order to maximize technique and craft and heat strategy—are a natural and obvious means to a pro-surfing end. It all tracks. Success stories abound, from Peter Townend, Rabbit Bartholomew, Ian Cairns, and others serving hard-earned lessons to each other and the generations that followed at the tour’s outset, to Williams and Florence today.

It’s all very sporty—but surfing isn’t just a sport, at least not for me. I consider myself competent, having sunk most of my life into being so. High level I’m not. I don’t compete. I’ve got no pressure to perform, no practical reason to examine the subtleties of my technique. My surfing doesn’t have to be good. It just has to feel good. That’s my means and my end.

As I examine this exercise from a remove—and from the artificiality of both the setting and the situation—I also realize the overwhelming majority of surfers aren’t sporty either. I can’t imagine pulling up to my local beach, friends waiting for me in the lot, waves pumping in the water, and stepping out of the car with my personal surf coach. I’d get eye-rolled, scoffed at, and joked into oblivion. It’d be, I’m afraid, a little try-hard—counter to surfing’s everyman values, disconcerting at both a cultural and aesthetic level, an affront to the purists.

“The long and short of coaching at any level is this: It’s been the single most destructive element of a century of surfer ethos—the individualism of lone wolves,” says Derek Hynd, who, along with being a former pro, journalist, and shaper over his 50-plus years in the game, was a coach to a number of surfers in the early ’80s, including Mark Occhilupo. “It’s a paradox, coaching, incredibly myopic yet so outrageously wide in span that it’s an industry unto itself. The surfing dream for kids and parents and coaches is collective conservative career engineering. Doesn’t matter the level—beginner, amateur, early pro. It’s a dull and duller stage-to-stage hook. The individual vanishes. Coaching kills art form.”

So, yes, I’ve got some reservations.

First, I’m worried it’ll steal the joy away from surfing good waves in pretty water and enjoying expensive things on someone else’s dime. Second, I’m sensitive. And in being coached, I’m going to be observed and studied and critiqued. I can’t think of anything more anxiety inducing for a recreational surfer like myself. But I’m already here in paradise, and my mother didn’t raise a quitter. She raised a masochist.

I try to articulate my concerns with Williams, at least the more personal ones.

“That’s why I like to work with surfers for a good chunk of time,” he says. “I want them to trust me, and I want to have their respect. That way, if I’m criticizing their surfing, it’s okay. I don’t come in hot. I don’t have a towel on my neck and blow the whistle. I don’t think that’s beneficial. But I know I have to be very honest, otherwise they’re wasting money on me. If I’m just giving them compliments, we won’t get anywhere.”

Williams sits back again, letting his shoulders drop.

“And once you start ripping, guess what?” he continues. “It becomes fun and then you start looking at surfing with less egg on your face.”

I know he’s being figurative. I look down at my plate anyway, where there was once an omelet, and lift my napkin off my lap. I wipe my face, just in case.

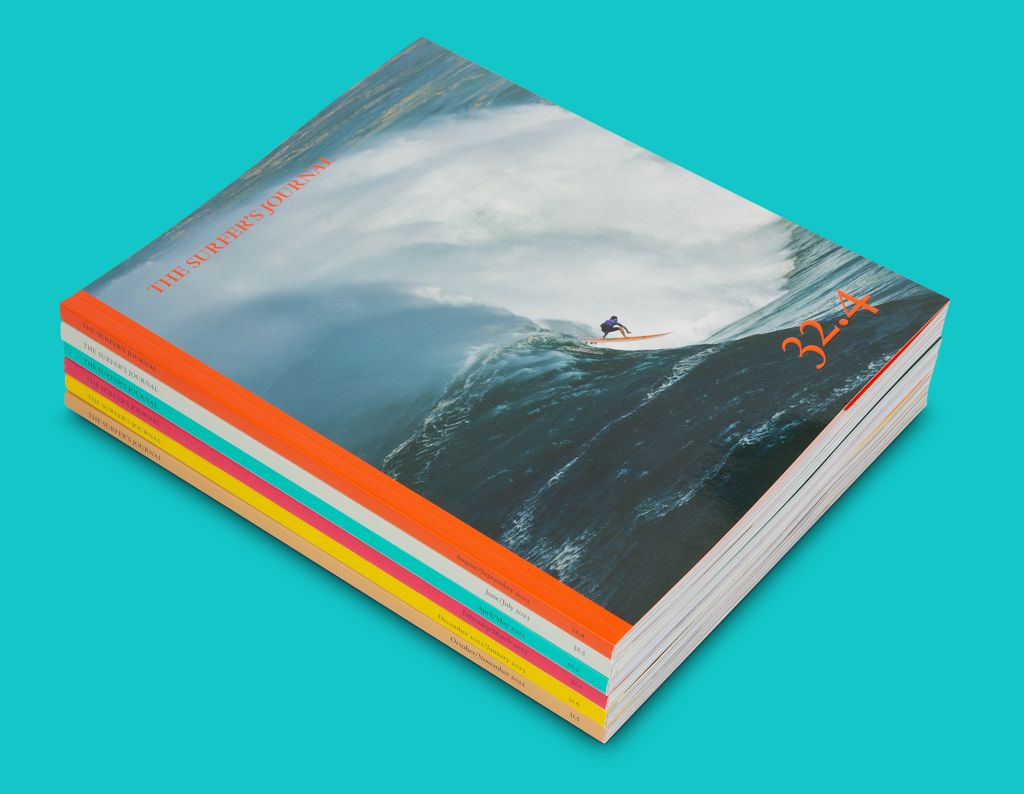

[Feature Image: Seminar sessions training grounds, the Maldives. Photo by Luke Patterson]

[To read “The Seminar Sessions” in full, become a TSJ member today by clicking here]